Participants in financial markets are engaging in a zero-sum game. Someone must underperform for any investor to generate excess returns over the market. Alpha works the same way; for every manager that has produced positive alpha, there must be someone that produced negative alpha. Yet, we know superstar managers who have made their clients rich. So, how were they able to do that, why is the average investment manager struggling, and will they likely continue to underperform?

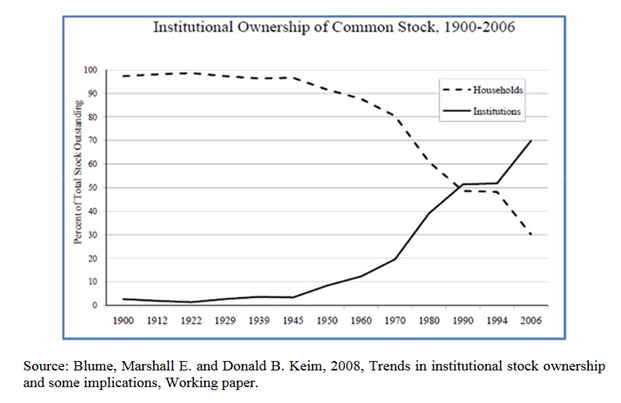

For an investment manager to outperform, he must have an edge. That edge could be educational, cognitive, or informational, among others. For example, insiders have always had an advantage; they have non-public information that can assist them in timing their purchases and sales of the company’s stock. This edge is asymmetrical and unfair, so the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 outlawed it. Another set of people that had an advantage in the early 20th century were those who knew how to read financial statements. Imagine a well-versed financial statements expert buying and selling securities with people who have a poor understanding of measuring a company’s profitability or the value of its assets (for example, Benjamin Graham versus your average 1930s market participants). Next, imagine someone who knows how to get around financials and can evaluate management’s character, skills, and cognitive biases (Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger versus your financially literate accountant). Looking at the institutional ownership chart below, we can see that until the 1990s, most market participants were retail investors, meaning average Joes’ owned and traded stocks. Most of those individuals were neither full-time investors, good financial evaluators, or great managerial judges. Because of their lack of expertise, individual investors were easy prey for skilled investors. With the rise of the mutual fund, the percentage of direct stock ownership began to slowly decline as more and more money began being managed professionally. A climax was reached in the 90s, as professional investors surpassed individual investors.

The rise of professional money management had some major market implications:

- Ever-increasing competition. Professional managers are full-time investors and more skilled compared to your average retail investor. As we know, there must be a seller in a market for every buyer. The increasing talent level meant it would be harder to find trades with “clueless” investors. This leads us to the second point.

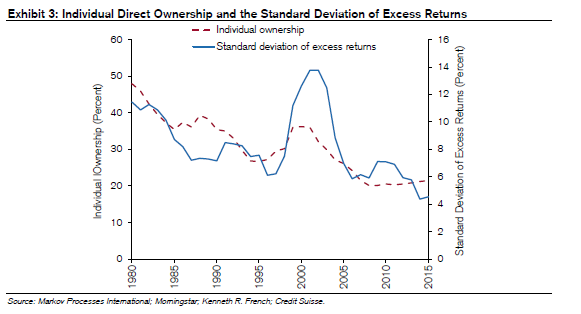

- Securities started trading closer to “intrinsic value”. This is because most of these managers attended the same ivy schools, learned from the same professors or investors (Benjamin Graham, Fisher, Buffet, etc.), used similar models, and arrived with similar ‘intrinsic values”. The end result means a decline in the standard deviation of excess returns (see chart above).

Warren Buffett warned Berkshire investors not to expect outperformance like in the 50s, 60s, and 70s. But, thanks to his and other top investors’ generosity in sharing their knowledge and skill, many current professional managers use similar techniques to select stocks.

In addition, the growing allocation of assets to index investing puts rising pressure on professional money management. Active market participants (professional managers and retail investors) help establish market prices by trading amongst one another based on their respective securities valuations. Index investing focuses on matching market-cap weightings of securities, the price set by those same active participants trading. Index investors are free riders, as they do not generate any additional market information and do not provide liquidity. As a result, index investing further heats up the competition. The active participants most likely to lose their assets to indexing are the poor-performing or unlucky active portfolio managers. This leaves fewer opportunities for the most skilled active investors.

In summary, do not expect active investing as an aggregate to outperform or generate excess alpha. It is impossible, as active investors charge higher fees, and as an aggregate, they can only match gross market returns. As a result, many savvy investors have transitioned to venture capital and private equity, as those markets have informational and structural asymmetries.